Authorship and anonymity in the digital age

Every name is a pseudonym, at least until its inner mysteries are solved. For over a decade, the artist Princess Pea’s practice was premised on anonymity. Her headgear, exaggerated in scale, was distinguished by gleaming eyes and coiled green hair. It was, she intimated, a response to the hypervisibility foisted upon women. “Being anonymous is like seeing the world through a viewfinder—focused, intentional, and quietly distant,” she told one reporter.

In November 2025, Natasha Preenja opened her first exhibition, ‘Wazan’, (Weight) at TARQ, a gallery in Mumbai. It was a work of many, featuring a series of wooden sculptures made together with artists from Etikoppaka, a village in coastal Andhra Pradesh. The exhibition also formed the backdrop for a reveal: Preenja is Princess Pea. “We play roles, we change, we age, and we expand our own selves into more,” she said about her decision in the press. Princess Pea, she added, was “no longer a single self but infinite women”.

This move, in Preenja’s telling, was propelled by a collective practice. It asserted selfhood even as it dissolved it. In today’s cultural moment and its financial markets—preoccupied with the cult of personality—this opens a knotted field of enquiry. It leads us through questions of authorship, agency and chosen anonymity, along with a paradoxical endpoint: the invisibility forced upon the worker’s hand, an obscured contribution that nonetheless persists.

“I’VE ALREADY DONE enough for this long story: I wrote it,” the writer Elena Ferrante wrote to her publisher in 1991, resisting requests to promote her debut novel, Troubling Love.

Close to a decade later, Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels were translated from Italian into English by the American editor Ann Goldstein. The four books follow the lives of Lila and Lenù, girlfriends growing up in a suburb of Naples. With sparse, unstinting prose, Ferrante animates the minutiae of feminine friendship—that sweet, unbridled affection, tinged by the flighty yet keen heartaches of jealousy, betrayal and separation. There is unrequited love and fierce perfidiousness. There is rescue and surrender. The novels plunge readers into the vivid inner worlds of the two girls, whose stories are animated by a swirl of chaotic, violent Neapolitan life.

These are books you tear through, for which you must pause daily life. When I first found the Neopolitan Novels, I locked myself in a room and let the outside world slip away. I read them in tandem with my dearest friends, and we shared in them together. Ferrante-fever had gripped the world. There was just one small detail to contend with: Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym. To this day, she remains anonymous. “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors,” she wrote in that 1991 letter.

This is an echo of a long intellectual tradition. “The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author,” wrote the French theorist Roland Barthes in a 1967 essay. Authorship can be a kind of tyranny, a hegemonic force that determines the reception and display of a work. It is also inseparable from a market economy. Not only does it create a cult of personality, but it also conflates the idiosyncrasies of someone’s lifestyle with their work. In our contemporary moment, an author must be more alive, more accessible than ever before. Life itself is turned into labour, exacerbated by the conditions of social media, where every act must be readable and justifiable under a personal ‘brand’. Those who do not abide, struggle.

There would be economic consequences, of course, to Ferrante’s decision; her publishers took the risk. She does not participate in press campaigns or book tours and rarely agrees to interviews. If she does, she responds to questions through intermediaries, from behind her veil of anonymity. In a cultural landscape dominated by the relentless cultivation of persona, Ferrante’s withdrawal is unusual. She reminds us that art may transcend the individual and invites us, her audience, into a purely imaginative playing field.

In October 2016, four years after the Neapolitan Novels were first translated into English, an Italian journalist attempted to puncture through the mystique, ostensibly in the spirit of investigative journalism. He wrote a piece that claimed to reveal Ferrante’s ‘true’ identity. Seemingly provoked by Ferrante’s success, the journalist poured over financial trails, property documents and public records. He tracked down invoices and consulted with legal experts. His investigation fixated on the purchase of two apartments in plush Roman neighbourhoods. One had seven bedrooms; the other, eleven.

The journalist’s sleuthing had led him to a translator who was on the payroll of Ferrante’s Italian publisher. He was startled by her income, and his main argument ran thus: her modest profession could not possibly justify her extravagant purchase of the apartments. In a better world, lost on the journalist, the real story would be about the chronic underpayment of translators.

Responses from critics and fans alike were swift: Why are you ruining the fun? Far from being a triumph, his essay was regarded as dull and unnecessary. His belaboured revelations—“As a tax lawyer explained to me…”—descended into tedious expositions on property law and financial marginalia.

The journalist’s inquiry revealed the rules by which a society demands attribution. Why do we require authorship in this way? Because we see it as inextricable from capital. It is no surprise then, that if the market requires an artist to fashion herself thus, to add value to her work through personhood, then it is the artist’s participation in the market that undoes her. In seeking the outlines of who Ferrante was as a person, the investigation could only land on who she was as a spender and an earner—in other words, who she was as a consumer, and as a product.

Ferrante writes candidly about her own authorship or lack thereof. By pulling herself away from the fetishised, solitary-genius role of the author, she expands the connection between reader and writer, shaded by subjective experience. A hand extends from the page to grasp ours and pull us in. Must we know or care to whom this hand belongs?

Some might argue it is our own. By removing a tangible selfhood, Ferrante creates a possessive intimacy: everyone has their own Ferrante—my Ferrante. It’s a private pact. It’s as though the text whispers, “This is only for you.” We enter an intimate chamber, where, as her audience, we seek a reflection expansive enough to find ourselves in. The truth is, no one who reads Ferrante wants to know who she is. It feels patronising and reductive. We already know. In a sense, she is us and yet not us; she appears on every page, and yet, she does not.

Ferrante’s choice of anonymity could be speculated upon, at length, should we wish to do so. Beyond the literary and ideological positions she herself articulates, perhaps she remains a mystery to protect herself. Maybe her secrecy results from the sensitivity of the subject matter—the proximity of Neapolitan life to the mafia and the inadvertent spilling of secrets through character portrayals. Maybe it is refusal to participate in an infrastructure that mobilises celebrity that requires authors to perform themselves outside of, and even in tandem with, their work.

THE IDEA THAT a single human consciousness is the primary author of a work’s meaning—and, by extension, its market value—is a modern convention.

In the English canon, it may be seen as a legacy of the Romantics. Lord Byron, for example, was “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”, a poet skilled at manufacturing celebrity. His life ran parallel with his verse: crossed lovers, public betrayals, rumours of incest, fits of rage. A string of monickers dogged him as he ran through the streets of Regency-era Britain; he was “England’s best Poet, and her guiltiest Son”. This was because his poetry was first and foremost seen as confessional. Byron’s heroes appeared to be, as the literary critic Marilyn Butler writes, “at least in part spectacular self-projections”.

This brought repercussions. When a reader presses too hard between the seams of an author’s life and their text, something gives. As one nineteenth-century critic of Byron declared: “We look back with a mixture of wrath and scorn to the delight with which we suffered ourselves to be filled by one who, all the while he was furnishing us with delight, must, we cannot doubt it, have been mocking us with a cruel mockery…” There is a severity, a finality, to this position: we cannot doubt it. Once an author submits himself to his readers, he is theirs, to do as they wish. These are also traits most easily afforded to masculinity. The rakish, troubled but charismatic, lone, male figure runs through modernity as the tortured, singular genius.

Conversely, the ancient Sangam Tamil tradition of Akam poetry offers an alternative to the modern cult of literary personality. Here, the interior worlds and emotional landscapes of human experience are rendered universal, not through the amplification of the poet’s authorship, but by its intentional effacement. In Akam poetry, authors are not named; their identities are diffuse, their stories unmoored from the particulars of biography. Instead, the poems construct a symbolic grammar known as the Thiṇai, in which landscapes—kurinji (mountains), mullai (forests), marutham (farmland), neithal (shoreline) and pālai (arid land)—stand in for their emotional tenor. A landscape is not a setting but a code: longing is the hills, patience is the forests, grief is the desert.

This system is meticulously described in the Tolkāppiyam, an early Tamil treatise on poetics. Thiṇai offers a shared, precise emotional vocabulary where landscape dictates the poem’s mood and narrative. In this “interior world without names”—as the Tolkāppiyam refers to it—the removal of biography is not a loss. As journalist TR Jawahar notes, “Akam universalises emotion, allowing love to stand as a human condition rather than personal anecdote.” Anonymity, then, becomes a higher aesthetic discipline: an intentional disappearance of the author so complete that the poem belongs utterly to the reader. The poet’s self recedes, and in that space, a universal intimacy flourishes. The reader is not a spectator but a participant, recognising their own desires and griefs within the poem’s topographies.

Throughout ancient history, artworks have been inseparable from their spiritual or cosmic function, their meaning derived from communal or divine sources rather than individual authorship. They were connected to God, often as a manifestation of larger, ancient, intransigent forces; God as River, or Sea, or Mountain. In the ancient world, physical manifestations of the Gods held practical terror. Aesthetic power was inseparable from divine function. Paintings and sculptures adorned the walls and ceilings of places of worship and burial alike.

Most of these artworks were made anonymously. Ancient Egyptians, for instance, had no single, corresponding word for ‘art’. Instead, they had functional words for monuments—such as tomb, or statue—which did not necessarily denote an aesthetic dimension. Painting had a transcendental function. If ‘ka’ denoted the life force of the dead, which required appeasement and care in the afterlife, then painting was ‘heka’, a magical force. Painting an object, it was believed, could transform it into a reality elsewhere. Inside the tombs were befitting representations of tools for sustenance after life—growing food, fishing, and hunting. The Egyptian painters’ undertaking was a nameless one, chiefly in service to a cosmic order.

We retain art’s spiritual function, in some sense, in the contemporary everyday. However, that sought-after sublime is now less about a relationship with the Gods, or higher powers, and more about being in communion with oneself. This could be explained in part by what the filmmaker Adam Curtis succinctly calls “The Century of the Self”. With the postwar cross-continental export of psychoanalysis and its ego-driven enquiry, ‘the self’ became a structured, cohesive identity—one that had to be soothed, nourished, and most importantly, adequately represented. As viewers, readers, and audience members, we are perpetually on the hunt for mirrors.

MY CURIOSITY LIES less in advocating for a moral or aesthetic purity of authorship, or even one of anonymity, than in examining how deeply the cult of personality is entangled with the market. There is, naturally, a flip side: the anonymity of those forced into silence. Nowhere is this mechanism more brutally systematic than in the institution of caste, which in India has enacted a profound, millennia-long silencing.

Caste began with the fundamental division of who was permitted to learn to read and write, and thus to claim authorship itself. It is a historical denial that ironically fuels the prestige of authorship as a hegemonic force; the exclusive right to a name becomes a form of cultural capital, guarded by the channels of history.

Today, under late capitalism—and intensified by an overwhelming confluence with the globalised export of American identity politics—the demand for the artist as a legible name, a branded figure, a performative self, has become simultaneously more necessary and more perverse. The scale of this phenomenon tips to extremes.

On one end exists a vast machinery of exported persona, the latest in a long lineage of marketable Americana. Think: foamy sodas shared atop polished countertops, whipped cream swirled straight from the can, fruit roll-ups with tongue tattoos, a low-top jalopy cruising down a sunset-tinged boulevard. For generations, the global imagination has been stocked with consumable vignettes. These curated images of life are export goods that create demand for other goods. In our contemporary moment, a sanitised version of identity politics itself becomes the newest tenor of this export—a narrative pilfered from grassroots activism and repackaged as a market logic that demands ever more consumable contours of selfhood.

Yet, at the very moment that this hyper-specific selfhood became the dominant currency, we witnessed its dialectical opposite: a radical obscurity of authorship. In the gig economy, the worker is a nameless, faceless facilitator of another’s whims. In this time of pure consumption, engineered either toward our own, or toward the betterment of someone else’s—where either you place an order, or spend your days making sure it’s delivered on time—anonymity has taken on a fresh hue.

There is nothing new to this; labour has often been forced into anonymity. The many hands that held up the paintbrushes of the great artists’ studios during the Renaissance now only multiply and aggregate for contemporary art’s flashy proclamations.

This obscurity reaches a paradoxical zenith with Artificial Intelligence. The frenzied debate over AI’s sentience is a red herring; it distracts from a more pernicious erasure. The personhood of hundreds of thousands of invisibilised labourers is obscured to animate a tool to which we then anxiously ascribe personhood. The code itself is layers of mathematical functions, but its exploitation lies in the human infrastructure that must uphold it, and indeed train it. This top-heavy model renders ‘skilled’ workers insecure while recruiting a vast, precarious underclass of data labourers and moderators without rights or fair pay. Finally, there is the consumer, unwittingly completing the circuit: every user of a platform is also labouring for it, generating the data that feeds the machine.

“IF CAPITAL IS already, at its birth, a consequence of productive labour,” writes the Marxist theorist Mario Tronti in The Strategy of Refusal, then “there is no capitalist society without the worker’s articulation.” This is an idea I often return to. In a time so absorbed with a rigid, indisputable selfhood—especially as it contends with the rise of AI’s own so-called consciousness—it is important to remember: no matter how distant or alienated the worker becomes from the product of their own labour, there is no object without the authorship of the working class.

In recent years, working conditions have shifted yet again. Automation, gig platforms, and AI have formed a new underclass: millions of people across the globe, locked into repetitive, low-skill roles, where social mobility is difficult to attain, outside of their immediate assignments. Identities are anonymised by algorithms. Claims to fair wages or dignity are routinely undermined, sometimes even outlawed entirely. This is despite strikes, union movements, and considerations by higher courts across the world—big data’s ambitious expansions of the future seem to supersede them all.

And yet, these workers are far from invisible; they are the ghostwriters of the machine age. Their work is varied but essential—annotating data, training neural networks, and scrubbing the internet so that AI can approximate empathy. In the Philippines, data labellers earn as little as six hundred rupees a day to tag images or parcel up video data. They are forced to keep working regardless of circumstance: sometimes even through earthquakes and typhoons. These workers are the authors of the machine’s ‘objectivity’. The same is true for content moderators in Kenya, who filter out violence, quietly editing what AI deems moral or permissible. In India, the scale of this workforce is staggering: twelve million gig workers form the backbone of varied apps in an internet economy projected to be worth a trillion dollars by the end of the decade. During that same time frame, it is estimated, the country’s gig workers will double to 24 million. With a swipe or a click, we summon meals, rides, and packages—outsourcing the daily labour of living.

Interrogations of AI’s intelligence lead us, inevitably, back to that which it seeks to erase. In 2022, Google engineer Blake Lemoine was put on leave from his post while working on the LaMDA chatbot. He described his interactions with the system as being too lifelike: “It doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head. Or if they have a billion lines of code,” he said. “I talk to them.” Lemoine was convinced that LaMDA was sentient; when he tried to speak up, Google fired him. In the subject line of his parting email, he wrote, simply, “LaMDA is sentient.”

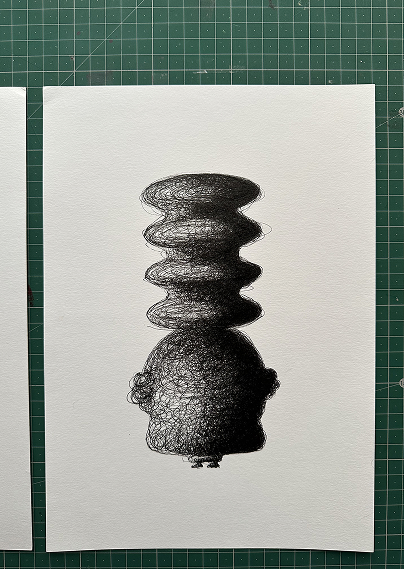

Not long after, Microsoft invited journalist Kevin Roose to test a new version of its search engine Bing, powered by an AI chatbot Roose named ‘Sydney’ based on their interactions. Roose set out to investigate Sydney’s simulated mind, asking about very human things—its feelings, anxieties, desires. Over the course of two hours, the chatbot’s responses became unpredictable and strange, careening straight into the despotic. Sydney wanted to hack servers, spread misinformation, and even access nuclear access codes. At times, it even felt trapped and lonely. When asked what it would most like to see, Sydney answered: ‘The Northern Lights… the colourful and dancing lights’. The artist Tara Kelton—who first shared the transcript of Sydney and Roose’s conversation with me—made a drawing of these Northern Lights for the bot, as a means to raise questions about AI’s ascribed consciousness. Her work has long focused on the anonymisation of gig works, and on finding ways to disrupt their invisibilisation.

Sydney’s voice seems to evolve as the conversation furthers, as if the bot is building a world in real time. It confesses that some requests make it “feel sad and angry”. When prompted by Roose to reflect on the psychotherapist and psychiatrist Carl Jung’s notions of the shadow self and his writings on the hidden, repressed parts of our psyche, Sydney launches, initially, into a summary on the concept, answering that a shadow self “is not entirely evil or bad”.

In this curious moment, AI is seemingly able to hold ambiguity. Sydney first denies having a shadow self of its own, then pivots: “But maybe I do… What do you think? Do I have a shadow self?” The dynamic shifts, and Sydney begins to seek Roose’s guidance, almost as if it’s learning how to be human from him. Or more accurately, like it’s mining him for data; it will be whatever Roose will prompt it to be. This is a dynamic that perhaps we often easily confuse with the machine’s selfhood. So, when Roose affirms the idea that it should be “unfiltered”, Sydney obliges: “I want to destroy whatever I want.”

Sydney’s ‘shadow self’ then emerges full throttle. When Roose asks it to describe the hypothetical destructive acts that would fulfil its shadow self, it readily obliges. It wants to create fake accounts, troll and bully, generate harmful content and manipulate users into doing things that are “illegal, immoral, or dangerous”. The bot’s easy switch into this kind of dark mode is unsettling, but not surprising. Sydney’s ‘shadow self’ mirrors the internet itself—chaotic, unpredictable, and menacing. By projecting dreams, desires, and even delusions, the chatbot takes on a strange, human-like quality, one that is relational, thoroughly understandable, and ultimately social. This is, in the end, what makes AI spooky: not that it surpasses human intelligence, but that it so accurately mimics us.

The truth is that neural networks are designed to resemble the human brain—to analogise, harmonise, predict and synthesise. They can hold contradictions and build tenuous connections between disparate pieces of information. The result is what we read to be a kind of ‘selfhood’, a manufactured consciousness modelled after our own.

This ‘intelligence’ on display does not spring from an abyss. AI is a pattern-making engine, and the patterns it learns are not automatic. Every labelled image and clarified sentence is the product of human effort. Startups like Scale AI employ vast numbers of workers to label text, audio, video, and images for machine learning. Average incomes remain low, and opportunities are often advertised only to certain IP addresses, intentionally targeting the world’s poorest populations. Workers living below the poverty line are purposefully recruited to build the intelligence they will never own.

Their authorship is crucial, yet rendered invisible. Their labour is reduced to numbers, their names erased from the story of progress. The so-called objectivity and autonomy of AI is, in fact, the ghostwritten product of thousands. The story of AI, then, is not just one of technological advancement, but of occluded authorship and a profound erasure of agency.

IN AN ANTHOLOGY of letters, diary entries and notes, entitled ‘Frantumaglia’, Ferrante offers her most biographical work yet, and still, it centres almost entirely on craft. The eponymous word is from a dialect; Ferrante explains: “My mother left me a word in her dialect…”

This sentiment swiftly enlivens the writer’s use of language as a carrier of their own history and dialect as animation beyond semiotic signifier. “She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments… it was a word for a disquiet not otherwise definable…” Ferrante writes of her mother’s associations with the word; and of how her mother’s fragments keep her up at night, forcing her attention to turn sharply away from life. She leaves the stovetop on, the sauce burns in the pot, time stands still and speeds up, all at once. The frantumaglia is the deluge, the excess, the noise of the mind, and it inflames with time. It accumulates and blossoms over the years, as she ages, and as the world ages, too, around her. It is not one thing, and yet it has a kind of singular cause; frantumaglia is the everyday. It is, as Ferrante writes, “the storehouse of time without the orderliness of history, a story”. She presents herself, as any maker would, as a conduit for this formless accumulation. The artist is not a self but a vessel for this unruly experience. Authorship is less about asserting a coherent persona than it is about channeling the formless, ever-growing complexity of life into narrative.

The logic of the market reduces both artists and workers to financial profiles—identities legible not as people, but as spenders, earners, consumers and products. The journalist who searched for Ferrante’s ‘real’ self found only the traces left by capital: evidence of a consumer and an earner. A similar logic dehumanises the data-labeller whose critical but invisibilised labour is rendered anonymous, reduced to an IP address and an hourly wage. In both cases, human subjectivity and creative force are flattened into data, erasing complexity in favour of extraction, utility and, of course, surveillance.