Pragati Mathur and the long arrival of textile as art

On a cool morning in Bangalore, Pragati Mathur sat under the shade of gulmohar trees working on a frame loom, making a piece titled The Healing Circle. Her fingers gently moved between the warp and the weft, sliding coils of copper wire. Around her lie yarns and fibres arranged by hue. The copper caught the light of the morning sun that filtered into the garden.

She studied her notebook and the sketches. Some pages had pieces of thread stuck on them. Each step was planned well in advance. “Conceptualisation is the largest part of my work,” she said while two other weavers worked beside her in meditative silence, following a sketch annotated down to the millimetre.

Mathur’s studio in Upper Palace Orchards in Sadashiva Nagar is five houses from her home, inside a seventy-year-old bungalow. It is warm in the winters and cool in the summers. The house is made of uncut granite, with Mangalore terracotta tiles, red cedar beams and Kadappa stone flooring. The garden surrounding the house is dotted with old fruiting trees—pomegranates, papaya, coconut, moringa and sitaphal. Soon a loom will find its space in a corner that lies empty.

A master weaver named Ashwathnarayan and his son, Devraj Ashwathnarayan, visit her most mornings with textiles they’ve developed, journeying from Chamarajpet, one of Bangalore’s oldest weaving neighbourhoods. Often, they listen to music as Mathur works on the frame loom. The weavers work on treadle looms. An installation is divided between the trio.

The Who’s Who in textile know this quiet process to be Pragati Mathur’s. She is, after all, a weaver, textile designer, and artist who began her career in the mid-1980s, weaving quietly at a time when the loom was not considered a medium, and textile was not recognised as art. In the fortieth year of her practice, she created one of her largest works to date, now installed and displayed as art at Bangalore International Airport.

The Healing Circle is conceived as a triptych rather than a single object, the work unfolds across three interlinked parts. At its centre is a large woven panel, its surface textured by a circular field of colour rendered in the shagpile technique. The palette draws on the elements—earth, fire, air, and water—while an outer ring of copper and gold signifies ether. The eye, she suggests, is meant to move gently across the surface. “It’s not an aggressive philosophy,” she said.

Flanking the central panel are two installations that extend onto adjoining walls, forming a DNA-like helix. One spiral, in blue with copper, silver, and muted gold, represents night; the other, in sunshine yellow, stands for day. Zardosi (traditionally associated with embroidery) is woven directly into the structure. “It’s very difficult to work with zardosi on a loom,” Mathur explained. “It expands. You can’t put it into a shuttle. You have to hand-throw it.”

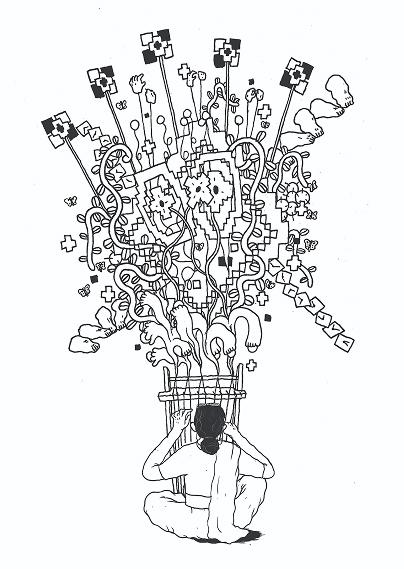

Created for India Art Fair 2026, the installation returns to a concern that has long shaped her practice: the growing estrangement between humans and the natural elements. “We pay more attention to emojis now,” she said. The circular form connects to an earlier work titled The Four Elements 02, a series conceived for a show titled White on White that was cancelled during the pandemic.

“The art world also goes through cycles of interest and obsession with varied media,” says Mayank Mansingh Kaul, a textile researcher, writer and curator.

It is Mathur’s first appearance at the India Art Fair. She repeats it, as if registering the strangeness of the fact. “It’s my first time… I’m glad the moment is now.” The statement hangs in the air, carrying an implicit question: Why now? Why not earlier? Why did textile take so long to be recognised as art in India?

FOR MUCH OF India’s modern cultural history, textile was positioned as heritage and labour rather than art. From the earliest days of Independence, revivalist movements—from Mahatma Gandhi at the charkha to Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s advocacy for state-backed interventions during the Nehruvian era—mobilised cloth as a moral and economic resource.

Even though handloom became central to the imagination of the nation, textile was rarely framed as a contemporary artistic language. It was instead preserved, documented, and institutionalised as part of a national project. “I don’t think art was a very conscious effort,” says Aditi Ranjan, a professor and author who helped shape early pedagogy at the National Institute of Design (NID). “The idea was to emphasise design as a socially relevant and economic tool… to assist in the development of groups of people, especially artisans.”

This emphasis on utility was even formally debated at the level of the State. Records from the Nehru Archives reveal parallel debates within government on handlooms versus power looms. In response to questions about whether mechanisation posed a “menace” amid cloth shortages, a note from Jawaharlal Nehru’s private secretary to the Yemmiganur Weavers’ Cooperative clarified that while power looms were not seen as a threat, the future of handloom weavers would be bleak without gradual adaptation.

Within this framework, the Weavers’ Service Centre was established in 1956 under cultural activist Pupul Jayakar. It sought to stabilise handloom through design support, technical expertise, and market access, cementing function as the primary lens through which textile was valued. “Institutions like National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) inherited this belief that design should directly serve the nation and economy,” says Rati Jha, the first dean of NIFT Delhi.

The consequences of this framework were enduring. Rta Kapur Chisti, a textile scholar and sari historian, notes that prevalence itself became a disqualifier: “When it’s still prevalent, it is not valued as art.” Textile was judged by how well it functioned—on the body or in the home—rather than by its capacity for abstraction or critique. “Utility disqualified textile from being studied as art,” Chisti adds.

Artists, however, were modernising the medium long before institutions developed the frameworks to acknowledge it. Even when figures such as Nelly Sethna produced work that defied easy categorisation, textile was read through the lens of tradition rather than proposition. “Galleries and institutions recognised textile work much later,” Ranjan notes. “Sethna’s work was discussed only recently. Otherwise, it was largely known in reference to her role at NID. Textile was valued more for what it represented—tradition, labour, nation—than for what it proposed as a medium.”

Mathur’s career in textile unfolded within this lag.

OF THE MANY places that shaped Mathur’s visual sensibility, few were as formative as Bundi, her mother’s maternal hometown in Rajasthan. In the 1980s, its streets were washed in natural pigments mixed with chuna, producing colours that were matte, breathable, and enduring. The desert light, the shimmer of mirrors, and the restraint of gota on saris and poshak left a lasting impression. The enduring impact of Rajasthan’s reds, pinks, and oranges, embedded itself early.

When Mathur was ten, her father’s posting took the family to London. Her adolescence unfolded against a backdrop of punk and pop art, with music from The Clash and The Beatles filling the airwaves. A progressive upbringing allowed her to travel across Europe with her sister, encountering museums and cities at a formative age. One memory stands out. Standing inside the Centre Pompidou in Paris, she found herself transfixed by a monumental installation of neon cones and spheres. “I remember telling my dad, ‘One day I’ll show here,’ ” she recalls.

During holidays back in India, her mother took her to textile markets, sourcing chheent fabric that was tailored into clothes for the girls. Worn in London, these garments elicited curiosity and admiration, quietly linking textile to identity and expression. Between Rajasthan and Europe, tradition and counterculture, Mathur absorbed a visual language that would later surface in her work.

THE JOURNEY BEGAN in Breach Candy, inside what was once a royal residential mansion. Its pink façade had passed from princes to pedagogy, becoming Sophia College, one of Bombay’s earliest institutions for women. In 1969, Indira Gandhi laid the foundation stone for a polytechnic there, introducing a textile department. In 1985, Pragati Mathur enrolled.

Sophia’s was a hive of activity, shaped by visiting faculty and rotating mentors who encouraged both rigour and experimentation. But the moment that clarified Mathur’s future arrived beyond the classroom, inside a newly opened gallery across the road.

She remembers walking in and stopping short. Light filtered through floor-to-ceiling windows onto yarns strewn across the floor. Loom parts appeared as sculptural fragments. On the walls hung works by textile designer Nelly Sethna, pieces that resisted easy classification. For Mathur, the exhibition proposed textile as inquiry.

“That’s when I knew,” she recalls. “With absolute certainty. I’d be a weaver.”

It was the first time that she saw weaving stretch beyond neat categories. While studying art history in her foundation year, encountering painting and sculpture firmly framed as art, her attention remained fixed on textile. She was uninterested in fabric as fashion or craft as revivalist exercise. Cloth, she sensed, could function as language and narrative.

Some of her earliest experiments emerged by accident. On a student trip, she encountered bamboo slats and painted them with delicate Japanese birds she had seen in a book. She wove them onto a frame loom and left the piece to dry overnight. By morning, the tension between warp and weft had caused several slats to flip, exposing their unpainted undersides. The work had altered itself. “It was perhaps then,” she said, “that the experimental weaver in me was born.”

Mathur’s training at Sophia’s was rigorous. Students learned to dress looms, mount samples, and translate sketches into structure on table and treadle looms. In classrooms, she heard stories about NID, its faculty, and its philosophy. Visiting practitioners, from Sethna to Rajendrasing “Rajen” Chaudhari, introduced students to experimental formats.

Her final examinations were conducted through the Directorate of Art, Maharashtra, at the Sir J J School of Art in Bombay. When the results were announced, she scanned the list from the bottom upward and did not see her name. She stopped midway and walked away. Her sister ran after her, shouting, “You’ve topped the class.” Mathur won gold. The next step was NID.

IT IS A particular conundrum that women of marriageable age must marry and instead of enrolling in NID, Mathur moved to Bangalore. Her wedding gift from her father-in-law was a loom, installed in the garage, with a configuration similar to the one she had used at Sophia’s. Soon after she reached Bangalore, she began work with the Weaver’s Service Centre, doing an internship for six months, where she encountered weavers whose knowledge came from lineage, not classrooms.

One such partnership in Bangalore proved formative. Working with a weaver called Sunanina from Assam, Mathur began translating her academic understanding of structure into cloth that was rooted in practice. The two produced beautiful cottons, and with access to fine silk in Bangalore, Mathur also worked extensively with silk waste, weaving motifs she already knew into unfamiliar material contexts. She began exploring unorthodox materials such as fibres and beads, continuing her experiments on the loom, including further explorations of the shagpile technique. As orders increased, so did the need for space, looms, and hands.

In the 1980s, Bangalore was in transition. Traditional weaving centres remained in Cubbonpet and Ganganagar, but the rise of power looms had affected the industry. Tucked away from this churn, Mathur’s unit grew steadily. She was joined part-time by Shankrappa, a master weaver from the Weavers’ Service Centre and, eventually, by eight traditional handloom weavers. Together, they produced saris, shawls, stoles, and yardage. Male weavers worked the pit looms, running lengths of cloth in the traditional Karnataka style. This was the ordained path for most textile graduates at the time, and Mathur followed it, even as she quietly tested its limits.

Colour was always her strength. She worked with silk, cotton, wool and mixed yarns, experimenting by weaving silk with angora, or incorporating gota. She adapted the Japanese sakiori technique, weaving repurposed strips into irregular textiles that registered structure. When she wove copper wire into saris, the textile became mouldable, adding engineering to drape.

She worked on bespoke yardages with leading fashion designers. Mathur’s textiles were exhibited in Bombay, stocked at Bungalow 8, one of the city’s earliest concept stores, and exhibited at Hubli in Calcutta. She worked briefly with Ogaan, a fashion boutique, for a while. Clients often stopped by her studio to discuss colour and form, often commissioning limited-edition pieces. It was small and slow, just how she wanted it. In the studio, her three young daughters played with frame looms and yarn.

The saris that emerged from this period were never everyday objects. There were gota pallas woven in, strips of fabric, experiments with lycra and cotton, and dented saris with stripes integral to the weave rather than embellishment or print. “These were actually works of art,” she says. This tension followed her through the years. The loom had become her place of enquiry, echoing German textile artist Anni Albers’ belief that abstraction has always existed in textile-making, from distillation and reduction of form to histories that run parallel to modern art itself.

AT TIMES, MATHUR’S explorations brushed against artistic acknowledgement, arriving unevenly and without a clear framework to hold them. One early piece, an odhna titled Colour Me India, drew from the reds, pinks, and oranges of Rajasthan. It was woven using an old tissue fabric that she acquired from an agency, its motifs cut out and relaid like a jigsaw on a base fabric. A brocade strip ran along the top and bottom, while the side border experimented with a weave of silk and zardosi, a material more commonly associated with embroidery and often resistant on the handloom. The piece was displayed at the Melbourne Museum and later worn by her eldest daughter during her chhatrachhaya, floating above her head as she walked to the mandap. “The textile now sits with her,” says Mathur.

Alongside these experiments, she was closely watching artists who were stretching the language of material. In the 1980s, she studied the work of Mrinalini Mukherjee, who worked with sisal fibre, banana and rope, and Monika Correa, who pushed the loom by removing the reed and allowing warps to float freely. From her student years, she recalls a college senior, Meera Tang, who was also working with textile as art. “But textile art hadn’t really come into a format at that point,” she says. There were others operating at the margins. A weaver from Ahmedabad, Rajen, who taught at NID and exhibited at Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay, showed that the loom could enter art spaces. Still, these gestures remained peripheral, and painting and sculpture continued to dominate the art canon.

“I’m not sure why it didn’t have the same impact as, for instance, a red dot on a canvas,” Mathur reflects. “But I think we’re there now. Today, textile art has firmly made a presence in the art world.”

There are signs that the ground beneath textile is shifting. “Never have we seen such prolific programming around fibre and fabric,” says textile designer Mayank Mansingh Kaul. “From exhibitions and publications to their inclusion in broader visual art conversations, this renaissance has been a long time in the making.”

A commission from the Chennai-based Suit Designs prompted Mathur to consider textile as sculpture. Looking to artists such as Ruth Asawa and El Anatsui, she began testing how cloth could occupy space. The breakthrough came with a wall panel made of copper wire, shaped like an achada and baked in the sun until its surface cracked and patinated like desert land. With that work, the practice shifted.

Further commissions followed, including Sacred Sands for JW Marriott, and later Navraspur, a ceiling-suspended installation at Bangalore International Airport.

Looking back, Mathur notes that the transition into art was not deliberate. It arrived through commissions almost accidentally, and grew into a language that is now inseparable from her practice.

As this language consolidated, after twenty years of running a commercial unit, Mathur shut it down and turned her attention inward. She consulted for brands, but her focus moved toward larger, more experimental textile works. For this phase, she partnered with master weaver Ashwathnarayan who she met at the Weavers’ Service Centre and his son Devraj Ashwathnarayan. Together, they began approaching the loom from a different prism. “Today I am innovating on the loom myself,” said Devraj, “but with reference to my ancestry, education and heritage developments.”

The process was not without friction. Weavers with generational knowledge carried habits honed over decades. “They have their own ways of doing things,” Mathur says, likening it to a recipe passed down in a family. She explains, “They’ll say, ‘Namak ko soongh ke dalna (Smell the salt before adding it)’ so you know the proportion will never go wrong. These subtleties will never be in a cookery book.”

Over time, Mathur’s ability to dismantle and reassemble the loom, like the ingredients in these recipes, to work through structure as well as intuition, shifted the dynamic. Doubt gave way to trust. Breakthroughs arrived through shared risk, when sketches replaced graphs and hours of labour were saved by trying something that was not supposed to work.

“Every time we have a breakthrough like this, there’s a shift,” she says. It is in these moments that textile moves beyond instruction and inheritance, becoming a living, negotiated language.

WHEN DOES CRAFT become art? Where do the two converge?

The problem lies in perception—art was celebrated while craft was a lesser cousin. Colonialism hammered this in while patriarchy reinforced the bias. What white European men made was art, and it was they who were admitted to the academies, while what women practised behind looms were “feminine” pursuits. Art was thus painting, sculpture, drawing and prints. Craft, irrespective of its aesthetic complexity, was simply utilitarian. But craft objects can qualify as art if they possess aesthetic attributes.

In The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, American art critic Arthur Danto suggests that art “detaches objects from the real world and makes them part of a different world, an art, a world of interpreted things”. Sally J Markowitz, in her essay The Distinction between Art and Craft, points out that we rarely interpret finely crafted benches, hand-thrown mugs, or woven shawls; we use them. Though we may contemplate them aesthetically and consider their form, tradition, or making, they remain “mere things” and do not demand interpretation the way paintings do.

The British Industrial Revolution wrecked Indian artisans and craftspeople, and is now acknowledged as one of the factors of the many nineteenth-century famines. It was also a contributory factor to the migration of indentured Indian labour to various parts of the world. The colonies suffered the brunt of the Industrial Revolution—they not only lost livelihoods but bought the same goods factory-made and imported from Europe.

BACK IN THE garden in Bangalore, that language is enacted daily. Mathur works on The Healing Circle alongside her collaborators, negotiating scale, tension, and resistance. “There are manipulations I can do on a handloom that cannot be done on a power loom,” she says. “There is a lot of hand-throwing. We try to push those boundaries of the mechanism.”

The labour remains slow and exacting, and each material insists on its own logic. Copper wire resists. Zardosi expands. Yarn behaves unpredictably under tension.

Alongside installations, Mathur continues to weave saris. One such work, Dahaad, is an engineered textile combining handloom chiffon and silk in a way few attempt. The chiffon section carries a lion’s mane motif rendered in zari, extending nearly 120 inches along the palla before dissolving into the pleats. The silk section is woven in a zero-twist yarn so soft it feels like air. The weights of chiffon and silk are matched so precisely that they appear identical. Satin borders, traditionally used to stabilise the garment at the neck and hem, are employed both structurally and visually, creating sharp contrasts of colour.

Mathur takes limited edition orders on pre-order, letting clients know in advance that these pieces take time. She considers them works of art. She does not repeat colours even if the motif remains, making each piece exclusive to the person who owns it. The labour is intense. “It’s too labour-intensive, too crazy, you have to put a kidney out there and then get it done,” A small capsule of six saris took six months to weave.

It is beautiful as an aesthetic. It is engineered. It is a sari, in the unstitched folds of which the distinction between art and craft disappears.